By David Hoffman, Jennifer Domagal-Goldman, Stephanie King, and Verdis Robinson

Let America be the dream that dreamers dreamed–

Let it be that great strong land of love

Where never kings connive nor tyrants scheme

That any man be crushed by one above. …

O, let America be America again–

The land that never has been yet–

And yet must be–the land where every man is free.

–from Langston Hughes, “Let America Be America Again” (written in 1935)

It has been a challenging couple of years for people in higher education working to fulfill the promise of American democracy.

Participants in the 2017 Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement Meeting grapple with higher education’s role in contributing to a thriving democracy. [Image credit: Greg Dohler]

Most of us have chosen our careers and commitments in part because of our profound optimism about the American experiment in self-governance. Our work with students in communities on campus and beyond reflects our belief that We, the People, appropriately oriented to our collective power, can work together across differences in background, experience, and perspective to promote the general welfare wisely and justly.Yet today our democracy is in crisis. New hostilities and old prejudices seem to be consuming the body politic. Confidence in our collective institutions and the nation’s overall direction has fallen precipitously. Higher education is under pressure to do more with less, and to focus student learning on workforce development and career preparation, potentially at the expense of civic learning and democratic engagement.

In the face of these pressures, it is tempting to yearn for simpler times, and to direct our work toward restoring what we sense has been lost. For decades, much civic learning and democratic engagement work in higher education, even the most innovative, has embedded a subtle retrospectivity: a longing for aspects of a partly mythic collective past. Higher education’s service-learning and nonpartisan political engagement initiatives have harkened back to a time when people spent more of their lives engaged in common activities rather than consuming content, and seemingly each other, through electronic screens. They have grasped for an elusive yesteryear of communal investments in projects and people, for the public good. With considerable success, educators supporting civic learning and democratic engagement have endeavored to regenerate the sense of empathy, shared responsibility, initiative, and courage celebrated in some Norman Rockwell paintings and in tales from the freedom movements of bygone days.

The four of us also feel that tug of nostalgia. Furthermore, we know that stories of democracy and civic agency from our collective past are vital cultural resources for anyone hoping to foster civic learning and democratic engagement today. Yet like one of the narrators of Langston Hughes’ Let America Be America Again, we recognize that even in better times, the promise of American democracy has never been completely fulfilled. Too many Americans have been kept at the margins. Even people not excluded from formal civic power by discriminatory laws and practices have been reduced to consumers and spectators of democracy by cultural conventions that have defined citizens simply as voters and volunteers, but only rarely as potential community-builders, civic professionals, innovators, and problem-solvers.

We believe higher education and its partners in communities across America need a vision of civic learning and democratic engagement for our time: oriented to the thriving democracy we have not yet achieved, but can build together. The influential 2012 report A Crucible Moment expressed such a vision in its call for weaving civic learning and democratic engagement into all of higher education’s work involving students. That call conceptualizes democratic engagement as a central practice in everyday life and relationships, not a particular set of activities undertaken on special occasions. It evokes John Dewey’s (1937) framing of democracy as a way of life that must be “enacted anew in every generation, in every year and day, in the living relations of person to person in all social forms and institutions.” In a similar vein, David Hoffman’s 2015 blog post Describing Transformative Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement Practices proposed that in order to transcend the paradigm of marginal, episodic, celebratory, and scripted civic engagement programs, higher education’s civic work must become more integral, relational, organic, and generative.

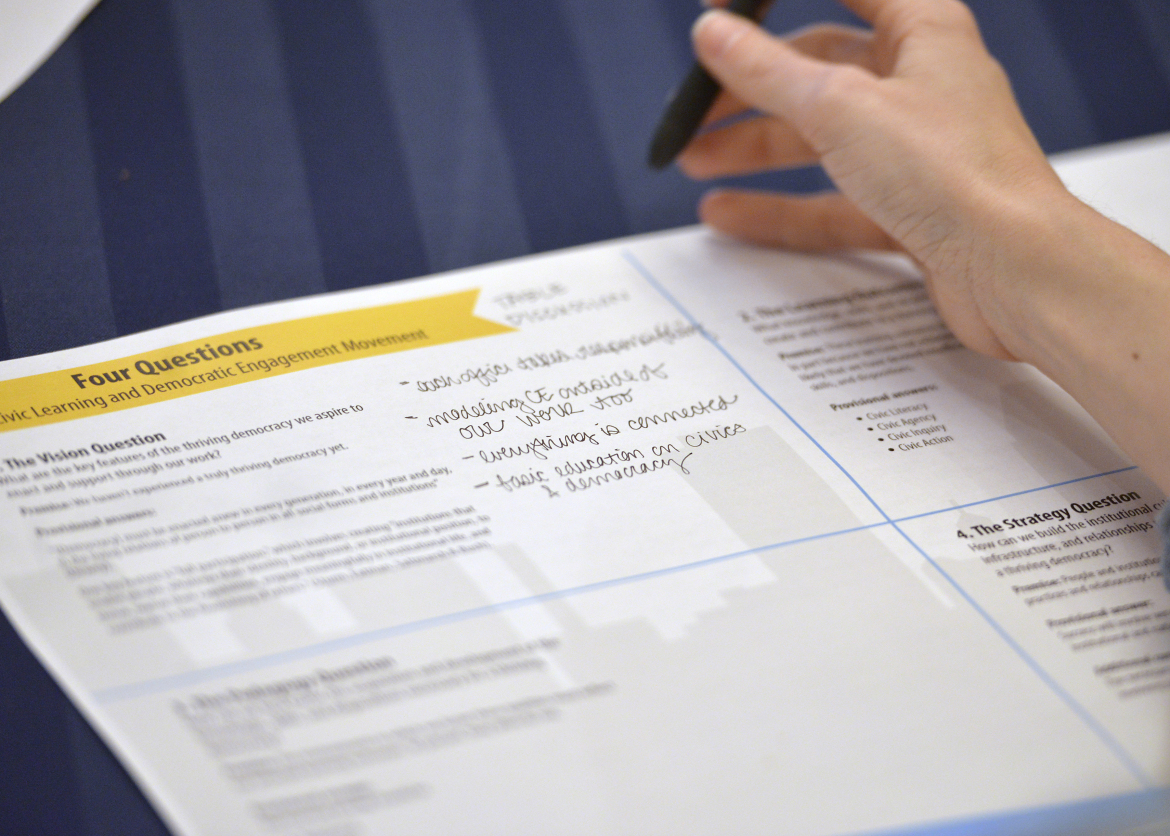

At the 2016 Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement (CLDE) Meeting in Indianapolis, Indiana, participants built on these insights as they imagined how people experiencing a thriving democracy in the year 2046 might look back at the intervening 30 years of progress. More recently, at the 2017 CLDE Meeting in Baltimore, Maryland, participants worked together to begin developing shared answers to four central questions facing higher education’s civic learning and democratic engagement movement:

- The Vision Question: What are the key features of the thriving democracy we aspire to enact and support through our work?

- The Learning Outcomes Question: What knowledge, skills, and dispositions do people need in order to help create and contribute to a thriving democracy?

- The Pedagogy Question: How can we best foster the acquisition and development of the knowledge, skills, and dispositions necessary for a thriving democracy?

- The Strategy Question: How can we build the institutional culture, infrastructure, and relationships needed to support learning that enables a thriving democracy?

Answering the four central questions facing higher education’s civic learning and democratic engagement movement. [Image credit: Greg Dohler]

Those energetic conversations, and the ideas they generated, are a very promising early step in an inclusive process of reimagining our collective work to meet democracy’s needs. In the coming months, we will share thinking emerging from within our networks and invite broad participation in refining tentative answers to the four key questions. At the 2018 CLDE meeting in Anaheim, California from June 6-9, participants will continue to shape and begin to apply our shared answers.Langston Hughes concluded “Let America Be America Again” with this injunction:

We, the people, must redeem

The land, the mines, the plants, the rivers.

The mountains and the endless plain —

All, all the stretch of these great green states —

And make America again!

We believe higher education is well-positioned to contribute to the fulfillment of this charge by extending and deepening our support for students as co-creators of a thriving democracy.

What are your thoughts and hopes for this emerging work? What issues should our networks be sure to consider as this planning process unfolds? Please share your comments.

References:

Dewey, J. (1937). “Education and social change.” Bulletin of the American Association of University Professors 23, 6, 472–4.

Hoffman, D. (2015, July 1). “Describing transformative civic learning and democratic engagement practices.” American Democracy Project (blog).

Hughes, L. (1994). “Let America be America again.” In A. Rampersad (Ed.), The collected poems of Langston Hughes (pp. 189-191). New York: Vintage. (Original work published in 1936).

National Task Force on Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement (2012). A Crucible Moment: College Learning and Democracy’s Future. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Authors:

David Hoffman is Assistant Director of Student Life for Civic Agency at the University of Maryland (MD) and an architect of UMBC’s BreakingGround initiative. His work is directed at fostering civic agency and democratic engagement through courses, co-curricular experiences and cultural practices on campus. His research explores students’ development as civic agents, highlighting the crucial role of experiences, environments, and relationships students perceive as “real” rather than synthetic or scripted. David is a member of Steering Committee for the American Democracy Project and the National Advisory Board for Imagining America. He is an alum of UCLA (BA), Harvard (JD, MPP) and UMBC (PhD).

Jennifer Domagal-Goldman is the national manager of AASCU’s American Democracy Project (ADP). She earned her doctorate in higher education from the Pennsylvania State University. She received her master’s degree in higher education and student affairs administration from the University of Vermont and a bachelor’s degree from the University of Rochester. Jennifer’s dissertation focused on how faculties learn to incorporate civic learning and engagement in their undergraduate teaching within their academic discipline. Jennifer holds an ex-officio position on the eJournal of Public Affairs’ editorial board.

Stephanie King is the Assistant Director for Knowledge Communities and Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement (CLDE) Initiatives at NASPA where she directs the NASPA Lead Initiative. She has worked in higher education since 2009 in the areas of student activities, orientation, residence life, and civic learning and democratic engagement. Stephanie earned her Master of Arts in Psychology at Chatham University and her B.S. in Biology from Walsh University. She has served as the Coordinator for Commuter, Evening and Weekend Programs at Walsh University, Administrative Assistant to the VP and Dean of Students for the Office of Student Affairs, the Coordinator of Student Affairs, and the Assistant Director of Residence Life and Student Affairs at Chatham University.

Verdis L. Robinson is the National Director of The Democracy Commitment after serving as a tenured Assistant Professor of History and African-American Studies at Monroe Community College (NY). Professionally, Verdis is a fellow of the Aspen Institute’s Faculty Seminar on Citizenship and the American and Global Polity, and the National Endowment for the Humanities’ Faculty Seminar on Rethinking Black Freedom Studies: The Jim Crow North and West. Additionally, Verdis is the founder of the Rochester Neighborhood Oral History Project that with his service-learning students created a walking tour of the community most impacted by the 1964 Race Riots, which has engaged over 400 members of Rochester community in dialogue and learning. He holds a B.M. in Voice Performance from Boston University, a B.S. and an M.A. in History from SUNY College at Brockport, and an M.A. in African-American Studies from SUNY University at Buffalo.