By David Hoffman, Jennifer Domagal-Goldman, Stephanie King, and Verdis Robinson

This is the second in a series of posts addressing the emergent Theory of Changebeing developed by higher education institutions that participate in the annual Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement Meeting, which includes a network of colleges and universities affiliated with the American Association of State Colleges and Universities’ (AASCU) American Democracy Project, The Democracy Commitment, and NASPA LEAD Initiative.

You can read the first blog post in this series here.

In recent decades, higher education’s civic learning and democratic engagement (CLDE) efforts have encouraged students to view themselves as having a significant stake in government, politics, and the welfare of people beyond their immediate social circles. As we described in a previous post, this focus has reflected a subtle retrospectivity, harkening to a partly mythic past of deeper affiliations within communities and with public institutions. Yet there have always been visionary elements in this work as well, directed at fulfilling, at long last, democratic possibilities to which Abraham Lincoln (1863), John Dewey (1937), Langston Hughes (1936/1994), and the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. (1963) famously alluded: government of the people, by the people, and for the people; democracy enacted through empowering relationships in every social institution; America as “that great strong land of love,” with opportunity for all; and freedom ringing from every mountainside, respectively.

In these challenging times for U.S. democracy, when the only sentiments that seem to unite people across party lines are feelings of powerlessness and alienation, higher education must lift up the visionary elements of its civic learning and democratic engagement work and give them renewed creative attention. With new clarity about our highest aspirations, we must develop strategies that can empower everyone as co-creators and co-producers of the thriving democracy we hope to enact and support through our work.

This new clarity can emerge in part from what Walter Brueggemann (2001) has called prophetic criticism: critical analysis of our everyday world that liberates our imaginations, enabling us to develop an energizing vision of an alternative future. What do you see when you examine our political culture, beyond a coarsening of public discourse and hardening of partisan positions?

Like some participants who shared their insights at the 2017 Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement Meeting, the four of us see how advances in technology have fueled the rapid adoption of the values and perspectives subtly encouraged by our apps and devices: blurring boundaries between reality and fiction; substituting status updates for deeper relationships; and conditioning us to expect infinite customization and instant gratification. Ironically, partly as a consequence of the ways in which we have become more thoroughly networked, Americans seem to be living increasingly as isolated, frustrated, individual consumers of civic life.

Participants at the 2017 Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement Meeting grapple with higher education’s role in contributing to a thriving democracy. Photo Credit: Greg Dohler.

This pattern is compounded by sometimes-dehumanizing norms and practices that have become pervasive features of our everyday world. Our national culture valorizes individual achievement, mastery, and command. Institutional cultures within U.S. higher education often reproduce and enact these values, in part by rendering knowledge into content, holistic learning into transactions, and people into objects to be shaped, managed, and measured through the application of context-independent “best practices.” In a time of scarcity within and beyond higher education, the imperatives of control and efficiency threaten to displace organic, relational, inclusive, and contextual approaches to knowledge creation, teaching and learning, problem-solving, and collective decision-making.

Most fundamentally of all, our failure as a society to embrace every person as fully human, morally equal, and entitled to full participation (Strum, Eatman, Saltmarsh & Bush, 2011) in civic life regardless of race, religion, class, gender, sexual orientation, age, ability, and other aspects of identity prevents us from pooling and leveraging all of our talents so we can thrive together.

There can be no single, simple antidote to the frustration and fatalism engendered by these features of our common world. Yet we can imagine a new era in which higher education’s civic learning and democratic engagement work helps to unleash the latent energy of Americans yearning for inclusion, connection, and collective agency.

Drawing from ideas shared by participants at the 2017 Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement Meeting, we envision that future, thriving democracy foregrounding interrelated values we have yet to fully enact collectively in our lives and institutions. Among them:

- Dignity – respect for the intrinsic moral equality of all persons

- Humanity – embracing environments and interactions that are generative and organic; rejecting objectification, and the marginalization of people based on aspects of their identities

- Decency – acting with humility and graciousness; rejecting domination for its own sake

- Honesty – frankness with civility; congruence between stated values and actions; avoidance of deceit, evasions, and manipulative conduct

- Curiosity – eagerness to learn, have new experiences, and tap the wisdom of other people

- Imagination – creativity and vision, including with respect to possible futures in which all of these values have become more central to our society and institutions

- Wisdom – discernment; comfort with complexity; non-manipulability

- Courage – fortitude to act with integrity even when there is a cost; capacity to thrive in the midst of ambiguity, uncertainty, and change; willingness to acknowledge vulnerability

- Community – belief that advancing the general welfare requires organized, collective work, enacted through relationships, partnerships, and networks, leveraging the diverse perspectives and talents of many people in order to produce benefits greater than the sum of their individual contributions

- Participation – action with other people to develop and achieve shared visions of the common good

- Stewardship – responsibility to act individually and collectively in ways that support others’ well-being, and the preservation and cultivation of resources, including norms and processes, necessary for all to thrive

- Resourcefulness – capacity to improvise, seek and gain knowledge, solve problems, and develop productive public relationships and partnerships

- Hope – belief in the power of people to bring about desired transformations; tenacity

In that new era, ordinary people will experience and expect full participation, not just in elections but in dialogue, problem-solving, organizing, and the creation of new laws, policies, and social resources for their communities, nation, and world. Rather than conceptualizing civics as confined in particular activities such as voting or providing voluntary service, Americans will build empowering democratic relationships and understand themselves to be potential civic co-creators in their workplaces, on their campuses, and in the everyday interactions that give meaning to their lives. In every institution, leaders will devote time and care to fostering environments and practices conducive to the fulfillment of core democratic values.

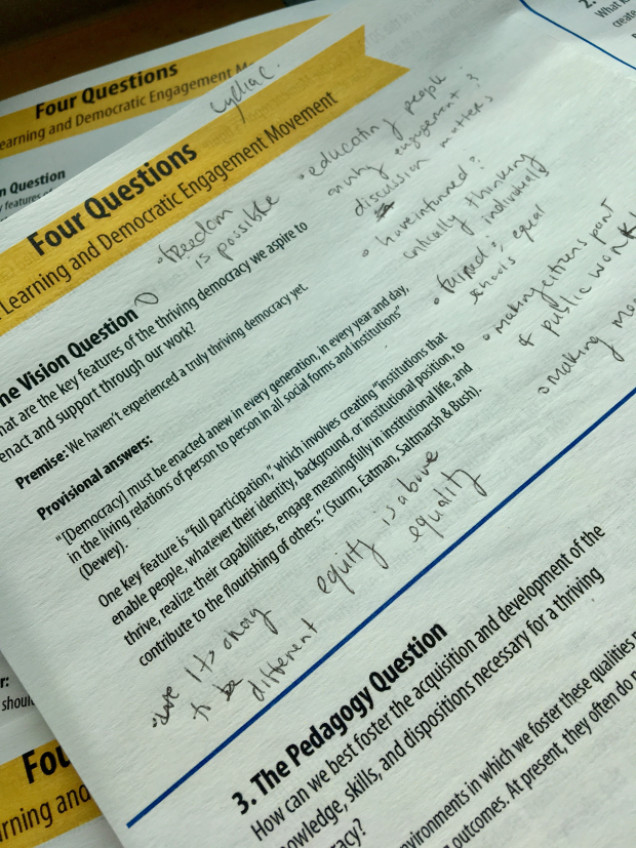

Responding to the vision prompt — what are the key features of the thriving democracy we aspire to enact and support? Photo credit: David Hoffman.

We believe higher education’s civic learning and democratic engagement work should be directed at enacting those values within our institutions, in our work with partners addressing community challenges and opportunities, and through the lifelong engagement of our graduates.

We look forward to the next stages in a collaborative process of refining and supplementing this sketch of a vision, including reviewing and engaging your comments on this post. The 2018 CLDE meeting in Anaheim, California from June 6-9, will be a particularly important opportunity to develop this vision together, along with the approaches and strategies needed to fulfill it.

What thoughts does this tentative vision spark for you? We know there are already initiatives in higher education designed to fulfill aspects of the vision we have described. How does your work do so? How could it go further? How can all of us grow and connect our work to refine, communicate and enact this vision?

References:

Brueggemann, W. (2001). The prophetic imagination (2nd ed.). Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress.

Dewey, J. (1937). “Education and social change.” Bulletin of the American Association of University Professors 23, 6, 472–4.

Hughes, L. (1994). “Let America be America again.” In A. Rampersad (Ed.), The collected poems of Langston Hughes (pp. 189-191). New York: Vintage. (Original work published in 1936).

King, M.L. (1963). I have a dream … Retrieved from https://www.archives.gov/files/press/exhibits/dream-speech.pdf.

Lincoln, A. (1863). Gettysburg address. Retrieved from http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/gettyb.asp.

Strum, S., Eatman, T., Saltmarsh, J., & Bush, A. (2011). Full participation: Building the architecture for diversity and community engagement in higher education (Imagining America Paper 17). Retrieved from http://surface.syr.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=ia.

Authors:

David Hoffman is Assistant Director of Student Life for Civic Agency at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC) and an architect of UMBC’s BreakingGround initiative. His work is directed at fostering civic agency and democratic engagement through courses, co-curricular experiences and cultural practices on campus. His research explores students’ development as civic agents, highlighting the crucial role of experiences, environments, and relationships students perceive as “real” rather than synthetic or scripted. David is a member of Steering Committee for the American Democracy Project and the National Advisory Board for Imagining America. He is an alum of UCLA (BA), Harvard (JD, MPP) and UMBC (PhD).

Jennifer Domagal-Goldman is the national manager of AASCU’s American Democracy Project (ADP). She earned her doctorate in higher education from the Pennsylvania State University. She received her master’s degree in higher education and student affairs administration from the University of Vermont and a bachelor’s degree from the University of Rochester. Jennifer’s dissertation focused on how faculties learn to incorporate civic learning and engagement in their undergraduate teaching within their academic discipline. Jennifer holds an ex-officio position on the eJournal of Public Affairs’ editorial board.

Stephanie King is the Assistant Director for Knowledge Communities and Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement (CLDE) Initiatives at NASPA where she directs the NASPA Lead Initiative. She has worked in higher education since 2009 in the areas of student activities, orientation, residence life, and civic learning and democratic engagement. Stephanie earned her Master of Arts in Psychology at Chatham University and her B.S. in Biology from Walsh University. She has served as the Coordinator for Commuter, Evening and Weekend Programs at Walsh University, Administrative Assistant to the VP and Dean of Students for the Office of Student Affairs, the Coordinator of Student Affairs, and the Assistant Director of Residence Life and Student Affairs at Chatham University.

Verdis L. Robinson is the National Director of The Democracy Commitment after serving as a tenured Assistant Professor of History and African-American Studies at Monroe Community College (NY). Professionally, Verdis is a fellow of the Aspen Institute’s Faculty Seminar: Citizenship and the American and Global Polity, and the National Endowment for the Humanities’ Faculty Seminar: Rethinking Black Freedom Studies: The Jim Crow North and West. Additionally, Verdis is the founder of the Rochester Neighborhood Oral History Project that with his service-learning students created a walking tour of the community most impacted by the 1964 Race Riots, which has engaged over 400 members of Rochester community in dialogue and learning. He holds a B.M. in Voice Performance from Boston University, a B.S. and an M.A. in History from SUNY College at Brockport, and an M.A. in African-American Studies from SUNY University at Buffalo.