By David Hoffman, Jennifer Domagal-Goldman, Stephanie King, and Verdis Robinson

This is the third in a series of posts addressing the emergent Theory of Change being developed by higher education institutions that participate in the annual’s Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement Meeting network, which includes a network of colleges and universities affiliated with the American Association of State Colleges and Universities’ (AASCU) American Democracy Project, The Democracy Commitment, and NASPA LEAD Initiative.

The first post described the CLDE Emergent Theory of Change and the process by which it is being developed; the second post identified key features of the thriving democracy higher education’s CLDE work seeks to support. These blog posts were also published on Forbes here and here.

Higher education institutions across the United States are doing creative, painstaking, hopeful work to prepare students for lives of meaningful engagement in their communities and democracy. Typically the focus of these efforts is on developing the knowledge, skills, and dispositions students need to cast informed votes, deliberate about public issues, appreciate perspectives and experiences they may not share, and serve as responsible stewards and change-agents.

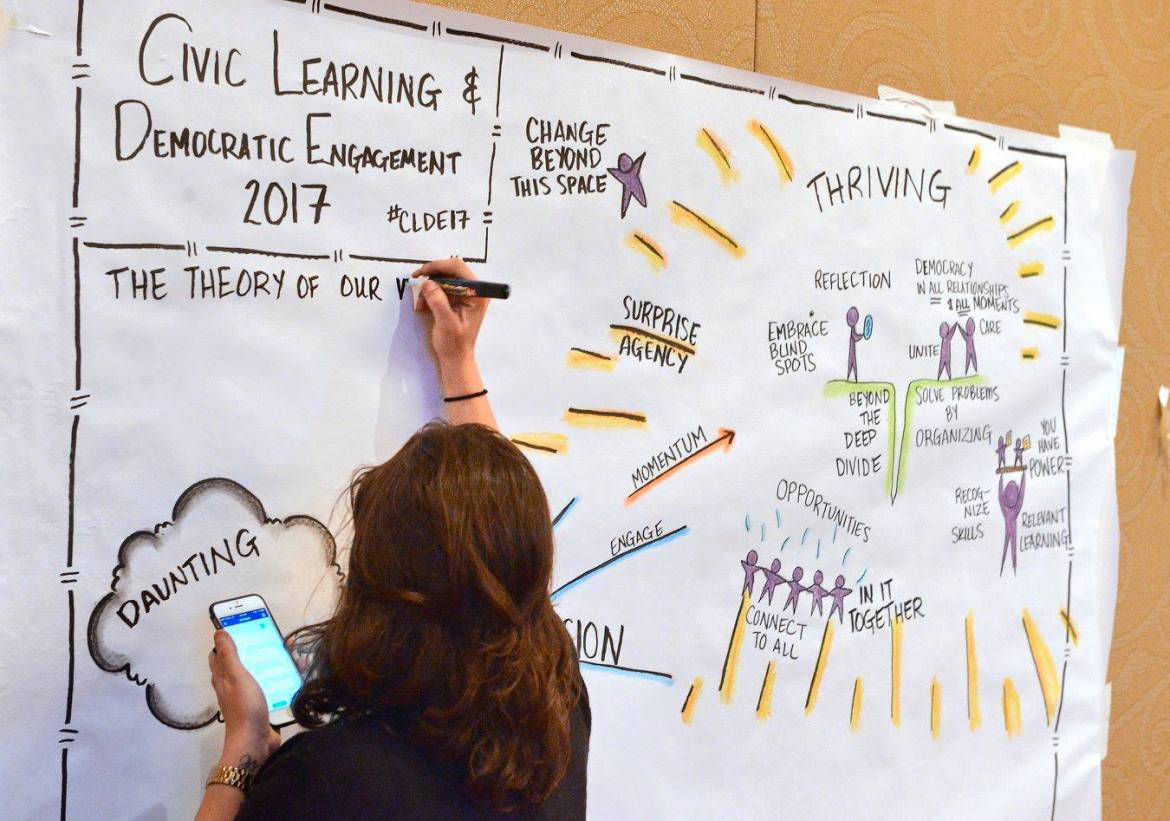

Live illustrator Ellen Lovelidge illustrates a plenary discussion about higher education’s role in contributing to a thriving democracy at the 2017 Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement Meeting. Photo Credit: Greg Dohler.

Yet if, as we asserted in a previous post, the collective goal of the CLDE movement in higher education is to support a thriving democracy grounded in values (dignity, humanity, decency, honesty, curiosity, imagination, wisdom, courage, community, participation, stewardship, resourcefulness, and hope) that support all of us in being fully human in all of our relationships and institutions, then we also must prepare students to attend to issues closer to home. Educating for engaged participation in our democracy must mean, in part, preparing and equipping people to recognize, navigate, address, and transform common, everyday cultural practices, in higher education and elsewhere, that inhibit us from adopting and enacting these values.

While institutions of higher education can be forums for learning and discovery that open new possibilities for human development and progress, they also can reproduce and amplify some of our national culture’s least democratic features, reducing students to consumers and objects to be manipulated and managed. Especially in this era of big data, on-demand services offering instant gratification, resource scarcity, and increasing student debt, colleges and universities are under pressure to deliver immediate, quantifiable results. Responding to this pressure, institutions may favor carefully designed and bounded learning experiences and disfavor organic, improvisational learning, which can get messy and produce unexpected outcomes. Yet the more they stick to scripts and constrain the scope of students’ agency, the less educational experiences can embody and communicate many of the core values of a thriving democracy.

Even beyond the boundaries of designed learning experiences, students may experience familiar, everyday aspects of campus culture as subtly restricting their sense of power, agency, and connection—as may we all. Students, faculty, and staff alike accept the constraints and demarcations imposed by the built environment, academic calendar, schedule of classes, the need to represent students’ achievements with scores and grades, the division of knowledge and exploration into disciplines, and all the hierarchies and ritualized interactions that are commonplace features of institutional life. We may also take for granted distinctions between campus and community, service provider and service recipient, citizen and professional, civic activity and everyday life, that are so deeply embedded in our culture that they seem given and eternal, as opposed to having been constructed by people. By us.

Some of this design work and boundary-creation is necessary: In order to foster learning, educators must gather students and create contexts for focused exploration. Doing so requires planning, coordination, and infrastructure. Yet in order to foster the democratic values we discussed in our previous post, institutions also must embody the civic ethos we hope will ultimately prevail in our society (Hoffman, 2016). Doing so is likely to involve relaxing our expectations relating to control and quantitative measurement, as well as intentionally eliminating some of the boundaries we have placed around our imaginations, relationships and learning processes.

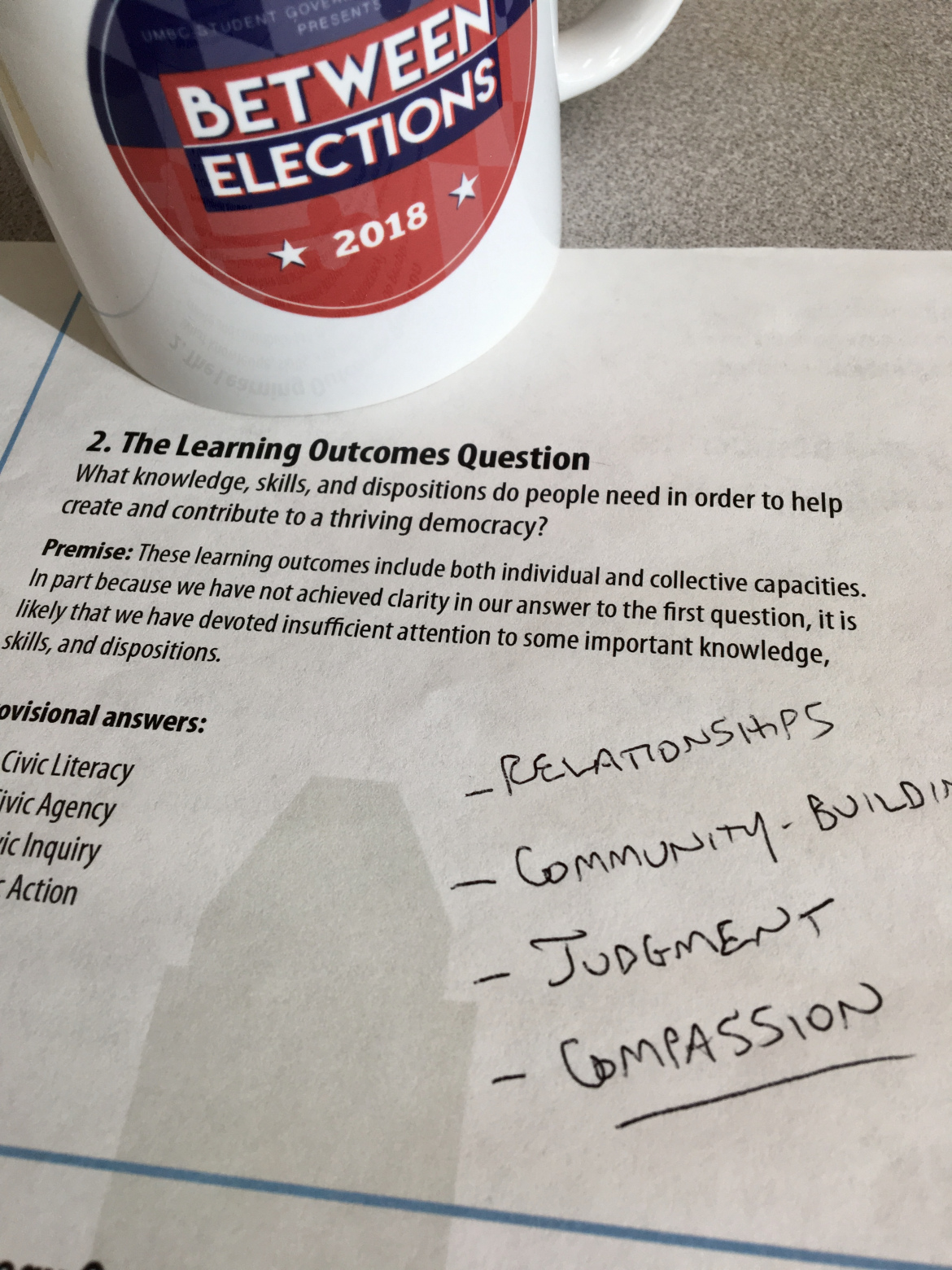

Responding to the learning outcomes prompt — What knowledge, skills, and dispositions do people need in order to help create and contribute to a thriving democracy? Photo credit: David Hoffman.

At the 2017 Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement (CLDE) Meeting in Baltimore, Maryland, participants discussed a list of individual and collective capacities that could serve as a guide for higher education in preparing students for lives of active, engaged citizenship. That list, drawn mostly from the influential 2012 report A Crucible Moment, included:

- Civic Literacy and Skill Building (emphasizing historical knowledge and critical thinking);

- Civic Inquiry (the practice of inquiring about and considering civic dimensions, public consequences, and different points of view);

- Civic Action (the capacity and commitment to work together across difference to solve problems); and

- Civic Agency (emphasizing vision and strategy, including with respect to institutional arrangements that can support collective action).

Based on feedback from conference participants, as well as our own reflections on the importance of “close to home” capacities needed to engage cultures and practices that inhibit personal agency and democratic relationships, we would rework and expand this list. We believe that the knowledge, skills and dispositions necessary for contributing to a thriving democracy can be expressed as the following civic capacities:

Civic Literacy and Discernment – encompassing individual and collective knowledge of democracy’s principles, contested features, history, and expressions in the U.S. and around the world; knowledge of the philosophical and practical dimensions of public policy issues, and understanding of different perspectives on those issues; and the capacity to distinguish factual claims made credibly and in good faith from error and propaganda.

Civic Agency – encompassing individuals’ self-conception as active agents shaping their world, as well as their capacities to recognize cultural practices, navigate complex institutions and undemocratic environments, imagine alternative arrangements and futures, and develop strategies for effective individual and collective action; and the collective capacities to develop a vision for our common life, recognize and respond to problems, make decisions generally accepted as legitimate, and foster the ongoing development of all of these capacities.

Real Communication – encompassing individual and collective capacities to engage in civil, unscripted, honest communication grounded in our common humanity, including about issues in connection with which individuals disagree based on their different stakes, life experiences, values, and aspirations; and the sensitivity and situational awareness to listen well and communicate authentically and effectively with different audiences.

Critical Solidarity – encompassing individual and collective recognition of the intrinsic worth and equality of all human beings, capacity to envision and identify with each other’s journeys and struggles, and disposition to work for the full participation (Strum, Eatman, Saltmarsh & Bush, 2011) of all Americans in our democratic life and against violations of people’s agency and equality.

Civic Courage – encompassing individuals’ willingness to risk position, reputation, and the comforts of stability in order to pursue justice and remove barriers to full participation in democratic life, openness to learning from others, including people with less formal training, positional power, and social status, and resilience in the face of adversity; and the collective capacity to embrace changes in cultural practices and institutional arrangements when such changes promote the general welfare and full participation in democratic life.

Integrity and Congruence – encompassing individual and collective capacities and commitments to enact democratic values in our everyday interactions, professional roles, cultural practices, institutional arrangements, public decisions, policies, and laws.

In upcoming posts, we will explore approaches to teaching, learning, and nurturing these individual and collective civic capacities, as well as strategies for building institutions that can support their development.

What do you think of this revised list, and the idea of focusing in part on “close to home” civic capacities like navigating and engaging institutional cultures and practices? How would adopting and pursuing the objectives on this list impact your work?

References:

Hoffman, D. (2016). “Ethos matters: Inspiring students as democracy’s co-creators.” NASPA (blog).

National Task Force on Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement (2012). A crucible moment: College learning and democracy’s future. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Strum, S., Eatman, T., Saltmarsh, J., & Bush, A. (2011). Full participation: Building the architecture for diversity and community engagement in higher education (Imagining America Paper 17). Retrieved from http://surface.syr.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=ia.

Authors:

David Hoffman is Assistant Director of Student Life for Civic Agency at the University of Maryland (MD) and an architect of UMBC’s BreakingGround initiative. His work is directed at fostering civic agency and democratic engagement through courses, co-curricular experiences and cultural practices on campus. His research explores students’ development as civic agents, highlighting the crucial role of experiences, environments, and relationships students perceive as “real” rather than synthetic or scripted. David is a member of Steering Committee for the American Democracy Project and the National Advisory Board for Imagining America. He is an alum of UCLA (BA), Harvard (JD, MPP) and UMBC (PhD).

Jennifer Domagal-Goldman is the national manager of AASCU’s American Democracy Project (ADP). She earned her doctorate in higher education from the Pennsylvania State University. She received her master’s degree in higher education and student affairs administration from the University of Vermont and a bachelor’s degree from the University of Rochester. Jennifer’s dissertation focused on how faculties learn to incorporate civic learning and engagement in their undergraduate teaching within their academic discipline. Jennifer holds an ex-officio position on the eJournal of Public Affairs’ editorial board.

Stephanie King is the Assistant Director for Knowledge Communities and Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement (CLDE) Initiatives at NASPA where she directs the NASPA Lead Initiative. She has worked in higher education since 2009 in the areas of student activities, orientation, residence life, and civic learning and democratic engagement. Stephanie earned her Master of Arts in Psychology at Chatham University and her B.S. in Biology from Walsh University. She has served as the Coordinator for Commuter, Evening and Weekend Programs at Walsh University, Administrative Assistant to the VP and Dean of Students for the Office of Student Affairs, the Coordinator of Student Affairs, and the Assistant Director of Residence Life and Student Affairs at Chatham University.

Verdis L. Robinson is the National Director of The Democracy Commitment after serving as a tenured Assistant Professor of History and African-American Studies at Monroe Community College (NY). Professionally, Verdis is a fellow of the Aspen Institute’s Faculty Seminar on Citizenship and the American and Global Polity, and the National Endowment for the Humanities’ Faculty Seminar on Rethinking Black Freedom Studies: The Jim Crow North and West. Additionally, Verdis is the founder of the Rochester Neighborhood Oral History Project that with his service-learning students created a walking tour of the community most impacted by the 1964 Race Riots, which has engaged over 400 members of Rochester community in dialogue and learning. He holds a B.M. in Voice Performance from Boston University, a B.S. and an M.A. in History from SUNY College at Brockport, and an M.A. in African-American Studies from SUNY University at Buffalo.